Public Capital: Industrial Policy and the Emerging Landscape of Economic Governance

By Gabriel Kahan // September 2023

Rumor has it, the neoliberal age is coming to an end. The doctrine of "free markets" has been revealed as smoke and mirrors, and many are coming to recognize that the state has always been there to prop them up — setting the stage, crafting the rules, and calming crises. But is it all just hype? Will today's governments translate their progressive rhetoric into progressive action?

To attempt an answer to this question requires an understanding of our current moment. For almost half a century now, national and local governments have rolled out the red carpet for private markets with the slashing of regulations, rampant subsidies, and the privatization of former public services. The explanation we were given was that the efficiency of profit-maximizing firms far surpassed that of the state. Be it housing, energy, or childcare, policymaking was, in effect, viewed as a matter best handled by shareholders and the wisdom of the price signal.

As the decades passed, however, there came a growing suspicion that this turn toward privatization was derailing the social contract in pursuit of narrow plutocratic interests. Jobs began to disappear and public infrastructure began to decay. Meanwhile, a chasm formed between the haves and the have-nots. Notions of the public good slipped from collective memory. The economic stability of the mid-twentieth century took on a hue of nostalgia, a brief era of mild prosperity followed by a set of broken promises. What happened?

In the plainest terms, our situation is one of mounting market failures. Rather than produce efficiently and allocate equitably, private markets have instead generated far-reaching social ills — as indicated by runaway inequality, ecological destabilization, stalling rates of growth, skyrocketing costs of living, dismantled labor protections, increased tax evasion, and the subjection of our democratic institutions to a new era of robber baron rent-seeking. As legal scholars Robert Hockett and Saule T. Omarova put it, our economic order is trapped in a profound collective action problem. What appears sensible and well-reasoned to individual market actors is spawning irrational investments, dysfunctional industries, and a deteriorating social fabric.

While such observations are by no means new, they are now arriving on the desks of those in high places. For the first time in decades, the leaders of high-income countries have broached the topic of industrial strategy, sparking a new policy landscape of increased state intervention. The aims of such policymaking are complex, catering to geopolitical and electoral rivalries as much as social welfare and ecological sustainability. Nonetheless, the result has been a stretching of the Overton window. To view private markets as engines of prosperity is no longer taken for granted. Public officials at all levels are being forced to reckon with a new set of debates concerning the proper relation between the market and the state.

This site is designed as one such contribution to these debates. As an ongoing publication series, it endeavors to provide a clear framework for understanding the current economic landscape confronting local policymakers across the US. Readers can expect analysis of ongoing policy experiments and how these compare to the various solutions on offer. Moreover, as a project of ProGov21 — a progressive policy library for local government — the series will provide resources and make concrete recommendations in the form of ordinances, resolutions, and related policy instruments.

This discussion, however, will avoid naïve optimism. Indeed, as some have commented, to interpret recent legislation as the end of the neoliberal era may be significantly misguided — with much of it potentially entrenching old political interests. As such, future contributions will critically assess the efficacy of specific policies, yielding a clearer picture of contemporary political economy and its inevitable imperfections.

As a prelude to such discussion, this first contribution begins with the question of institutional design. That is, what institutional arrangements — be they public, private, or something else entirely — are best equipped to govern economic life given the challenges we currently face?

Beyond Private Markets

If an economic system is defined by a set of actors pursuing divergent self-interested agendas, what set of behaviors is its polity willing to tolerate? This is the collective action problem of private markets and the question underlying all industrial policy, old and new.

More concretely, what role should the state play in crafting, demarcating, and regulating markets? Is it a simple matter of maintaining "healthy competition," as exemplified by anti-trust law? Is it a matter of adding cushion to the turbulence of the business cycle, as exemplified by the interest rate policies of central banks? Is it a matter of guiding private investors toward developmental goals, as in the case of subsidies, public R&D, and other instruments of de-risking? Or is it a matter of decoupling critical industries from market imperatives entirely, as in the case of public transportation systems, energy grids, and housing projects?

With such an enormous breadth of policies available to governments, a framework is needed to categorize and compare. But where to begin? On what grounds can we draw a throughline between such diverse interventions? Central to this analysis, I argue, should be an examination of the institutional arrangements through which economic life is governed. One way of doing this would be to pay attention to how decisions over the allocation of resources are made.

In the case of private markets, investors behave as unelected economic planners engineering specific development within and across communities. Such an institutional arrangement provides limited accountability and often prioritizes strategic rent-seeking above high quality social provision. As markets grow in scale and complexity, the exigencies of competition often trump all other objectives. Individual investors find themselves incapable or disinterested in the cross-sector coordination required for large-scale developmental goals. Here private capital — in the broad sense of finances, materials, equipment, and labor — is oriented around the narrow logic of accumulation, rather than long-term social need. The tendency is thus one of market failure.

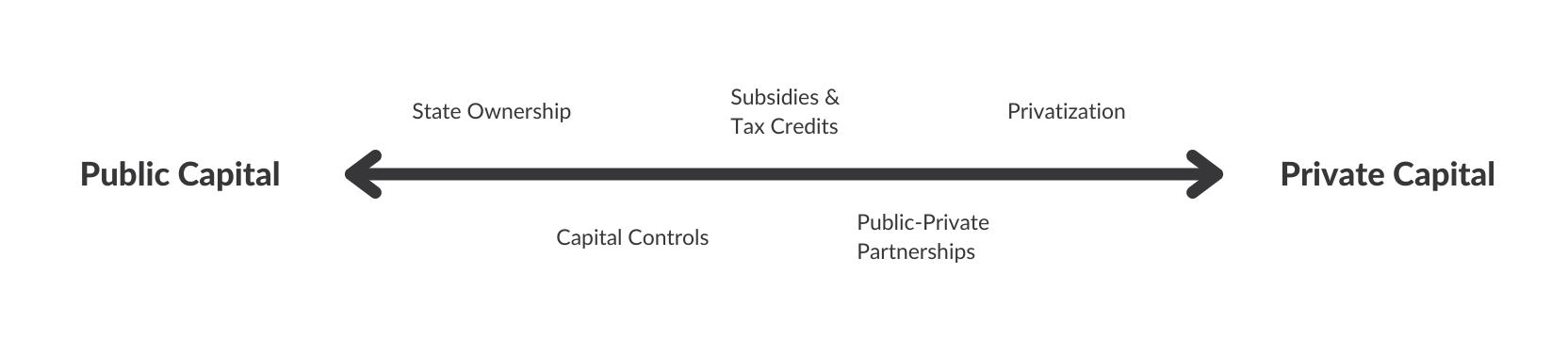

To move beyond this what is needed is a clear sense of the possible responses to such tendencies. As Figure 1 shows, this can be visualized as a spectrum. The assumption here is that for most jurisdictions today capital must be governed by some set of institutions, be they public, private, or some combination of the two. In the case of public economic governance, the state's role is prominent. Through strong disciplinary mechanisms or overt ownership, it actively supervises how capital is allocated and to what ends. In the case of private economic governance, the state's role is minimal, existing to maintain the basic parameters of commerce. Thus it is the middle of the spectrum that designates hybrid interventions. These would be various combinations of public and private economic governance, such as attempts made by the state to incentivize private investment in specific resources, sectors, or geographies.

Figure 1. Varieties of Economic Governance. Note that the included policies are meant as examples, not an exhaustive list. The purpose of this publication series will be to explore these in greater detail.

To be clear, the spectrum above is meant only as a heuristic for comparisons between policy agendas and their respective advantages in combatting and transforming market failures. However, the right-hand side of the spectrum signifies an approach that has come to dominate economic governance for many decades now. It captures the essence of what is meant by the neoliberal approach to policymaking. As such, it is a well-trodden path that would greatly benefit from consideration of alternatives. While private markets themselves are not devoid of utility, the actors that rule them have proven incapable of maintaining a coherent and healthy economic order. In their place, new horizons of economic governance must be considered.

Building the High Road with Public Capital

To take seriously the future of economic governance entails contemplating the role of public capital in economic policy. That is, what forms of public finance or state-managed programs should be used alongside, or in place of, private forms of capital? If the goal is to allocate resources productively, equitably, and sustainably, a variety of strategies emerge.

There are many instances, for example, where local governments are entrusted with the ability to define the rules of the game for entire sectors within their jurisdiction. Is it a matter of guiding these sectors in desirable directions? Is it a matter of supplementing them with a strong public sector? Or is a matter of removing certain allocation from the market mechanism entirely? The advantages, disadvantages, and intersections of these approaches will feature prominently in future contributions. Moreover, we might call these high road strategies. As the High Road Strategy Center describes it, this approach to policymaking emphasizes the role of public infrastructure and democratic institutions in generating lasting economic prosperity.

For now, then, the point is that public capital, in one institutional form or another, will define the horizon of possibility for economic policy in the years to come. As such, it is also the title of this publication series — a reminder that the ownership, management, and cultivation of capital is not the sole prerogative of private actors.

Don't miss the next post!

If you like what you read, consider subscribing to ProGov21's newsletter. You'll be the first to hear of new contributions to Public Capital, alongside featured briefings on local policy solutions to today's most pressing dilemmas.

To learn more about ProGov21, click here.